About

Programs

Enhancing Literacy and Language Instruction

Support the Center’s Research and Activities

Research Initiatives

Literacy and Language Development Clinics

Purdue’s Literacy and Language Development Clinics (LLDC) offer an array of service options tailored to individual school populations’ needs, and resources for literacy and language development for grades K-6. Clinical services include needs assessment, screening, and one-on-one Intervention.

Teacher Release Project

The Teacher Release Project offers school districts up to one hour of teacher release time per month per classroom while Purdue educators lead classrooms in research-based reading and writing activities (given parent/guardian permission and child assent).

Project PUEDE

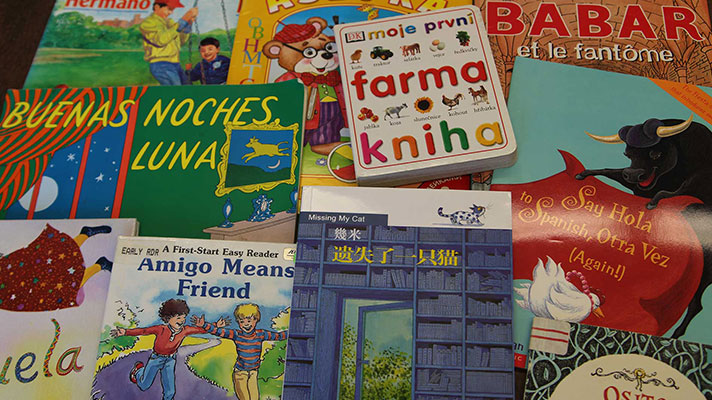

Project PUEDE (Professional and Parental Understanding for Equity in Dual Language Education) enhanced the instructional and family engagement capacities of pre- and in-service teachers, administrators, and family liaisons in Indiana in dual language (DL) education through licensure and adequate Spanish proficiency.

Leveraging the Lectura y Lenguaje

Leveraging Lectura y Lenguaje enhanced the overall literacy and English language (EL) development capacities of elementary pre- and in-service educators, administrators, and family liaisons in Central Indiana schools, creating a stable EL infrastructure.

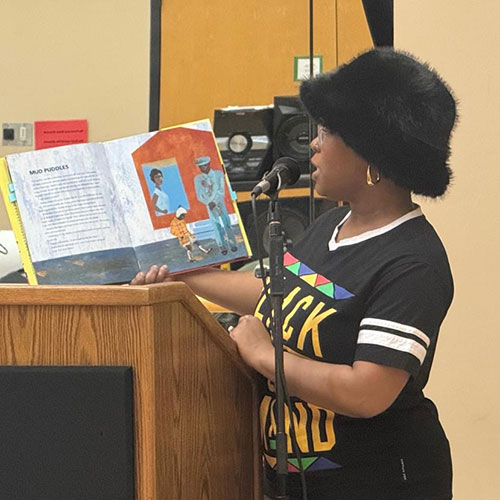

Research Briefs

CL2EAR Briefs are a series of short reports that address topics of interest related to literacy and language education. They are intended to provide educators, administrators, and policymakers with an overview of research and practical applications on current issues in the field. CL2EAR Briefs can be accessed below.

To save or print these briefs, please fill out the CL2EAR Research Brief Request Form.

Research Brief – Learning to Read while Learning a Language: Reading and English Learners

Trish Morita-Mullaney, Ph.D.

Associate Professor, Purdue University

February 2025

The Science of Reading (SOR) is intended to benefit all children as they develop a strong foundation in reading. For a growing number of students who have proficiencies in languages other than English, how they experience SOR classroom activities differs. Students who are learning English as an additional language come from a variety of language backgrounds and enter at different levels of English proficiency, ranging from beginner to advanced. This research brief provides a linguistic landscape of Indiana’s K-12 students, followed by a review of the research on how certain components of reading (phonemic awareness, phonics, and fluency) are different for identified-English learners (ELs).

The linguistic landscape of Indiana’s K-12 students

Indiana is home to students who speak 296 different languages, most of whom are born in the United States and whose parents are devoted to both their home language maintenance their development in English. The current population of English learners who have a language background other than English accounts for over 148,000 students with 93,625 students requiring English language development services by certified personnel (Morita-Mullaney, 2022). Indiana requires that when a district has at least 30 identified-ELs, then a licensed English as a Second Language teacher must serve as their teacher of record (McCormick, 2019).

Supreme Court course cases ensure that identified-ELs receive an accessible and meaningful education. Lau v. Nichols (1974) states that the “same education is not an equal education” and as such, meaningful efforts and resources must be furnished to make such education accessible. Castañeda v. Pickard (1981) goes a step further stating that identified-ELs must have an education that is 1) based on sound educational theory for ELs; 2) adequately resourced; and 3) found to be effective. Several federal statutes articulate a legal right for identified-ELs to a “meaningful and reasonable” education, including the Title VI of Civil Rights Act of 1964, Equal Educational Opportunities Act of 1974, and the Every Student Succeeds Act of 2015 (ESSA)–the federal authorization within the Elementary and Secondary Education Act. Within these statutes, districts and schools commit to provisions of making instruction accessible to them while they are moving through the English language development process and holding fast to the three-pronged rule as articulated above in Castañeda.

How reading is different for identified-ELs

Phonemic awareness, phonics, and fluency are foundational reading skills. This section reviews three key ways in which developing these skills is different for identified-ELs.

Phonemic Awareness

Phonemic awareness is the capacity to identify sounds and manipulate them. Typical activities related to phonemic awareness include rhyming. For example, a teacher might have students say “mop” and “top” and recognize that the initial sounds are different. For identified-ELs, they are accustomed to hearing different phonemes in their home languages; thus, they draw upon those more familiar sounds to connect to English. When identified-EL students are asked if a sound is correct, they may be unsure because for them, it is not yet familiar. Because of these linguistic differences and challenges, ELs are often seen as “at risk;” yet when we look at the principles of second language acquisition, they are doing what linguists would expect – using their existing and sophisticated linguistic knowledge to receptively hear sounds and re/produce them in ways that is shaped by their language histories. There is a linguistic logic to what they hear and express.

Phonics

Phonics involves the matching of sounds to the symbols that represent them by connecting sounds to individual or groups of letters. More specifically, how students move from simple phonemes; to the graphemes they see in text and how they make such correspondences is at the core of phonics instruction (Ehri, 2020). As with phonemic awareness, ELs may not be able to discriminate between similar sounds. For example, for the letter ‘a’ in the word ‘cat’ and ‘had’ sound similar, but the word ‘rare’ and ‘care’ have a different sound production. While these differences are noticeable to an English majority speaker, such sounds may not be discriminated as well by an EL student at the earlier stages of their English language development. Further, English does not have an exact sound to symbol correspondence, often complicating English phonics learning when ELs are at the earliest stages of their English language development (e.g. level 1 newcomer).

Fluency

Reading fluency is described by three key characteristics:1) accuracy; 2) pace; and 3) prosody/expression. In practice this often requires students to read passages accurately, at a decent pace and that they do so with voice modulation and expression. For identified-ELs, their understanding of particular letters and sounds is mediated by their first or other languages and students draw upon these resources, impacting how accurate they may sound when reading. For example, if a Spanish-speaking reads the word “jam” as “ham”, this is mediated by the letter “j” having an /h/ sound in Spanish, so for them, this is an accurate production. Yet, in practice, this reading is rendered as inaccurate and instructional placements are made without this linguistic understanding of their first language.

For pace, if a child reads too slowly it will impede comprehension; so a relatively quick cadence is needed to facilitate understanding (Rasinski & Padak, 2013). Yet, research of identified-ELs shows that while they do read more slowly, this does not necessarily hamper comprehension (Ramirez, 2000). ELs engage in the sophisticated metalinguistic process of making connections in their other languages to English, often impacting the pace and rhythm of their reading.

Expression or prosody within second language acquisition comes at a later stage in English language development process. How language is used in different contexts and social situations, includes using and adapting language, as well as the ability to pick up on nuances that convey a particular voice to a reading (Lightbown & Spada, 2013). Social expectations and understandings vary across languages and cultures, so even if you are quite proficient in another language, understanding the social cues of expression come much later in the language development process. Thus, when ELs have a monotone narration as they read, they can be identified as lacking fluency in reading, when it is really an indicator of where they are in the English language development process.

Conclusion

Many decisions are made about ELs’ performances within SOR related activities that do not consider their level of English proficiency. Furthermore, much SOR content is not typically a part of teacher preparation, providing teachers with one set of tools for interpreting ELs’ performances. For researchers and practitioners considering ELs within SOR related activities, careful attention should be paid to the principles of second language development, understanding their systems of their first language (e.g. what sounds differ or are absent in their first language) and recognizing that English language development does not always keep pace with the linguistic demands of reading.

References

Castañeda v. Pickard, 648 F. 2d 989 (5th Cir. 1981).

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Pub. L. No. 88-352, 78 Stat. 241 (1964)

Ehri, L. C. (2020). The Science of Learning to Read Words: A Case for Systematic Phonics Instruction. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(S1), S45–S60.

Every Student Succeeds Act, Pub. L. No. Public Law 114-95, (2015).

Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 (1974). (1974).

Lightbown, P., & Spada, N. M. (2013). How languages are learned (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

McCormick, J. (2019). English Learner Teacher of Record Frequently Asked Questions. Indiana Department of Education, Indianapolis, IN.

Morita-Mullaney, T. (2022). Reckoning with Hammers and Mallets: Indiana’s Approach to Licensing English Learner Teachers. Indiana Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages, 19(1), 76-101. https://doi.org/10.18060/26562

Ramirez, J. D. (2000). Bilingualism and Literacy: Problem or Opportunity? A Synthesis of Reading Research on Bilingual Students. Office of Bilingual Education and Minority Languages Affairs (OBEMLA), Washington, DC.

Rasinski, T. V., & Padak, N. (2013). From fluency to comprehension : powerful instruction through authentic reading (1st ed.). Guilford Press.

Research Brief – Knowledge of Morphological Structure and its connection to reading and writing

Chenell Loudermill, Ph.D., CCC-SLP

Clinical Professor, Purdue University

April 2025

Within the body of literature that provides sound evidence of reading and writing development and disorders, knowledge of morphological structure has been found to play a crucial role. Specifically, awareness of morphological structure (e.g., morphological awareness) serves as an avenue for improving vocabulary, word reading, spelling and reading comprehension. This research brief provides an overview of morphology and morphological awareness, why it is important for reading and writing, how morphological awareness contributes to the aforementioned skills, and considerations for non-native English speakers.

Morphology and Morphological Awareness

In language-spoken or written-morphology refers to the study of how words are formed. As spoken and written language develops, we learn to talk with words but we rarely talk about how words are formed. The English language is morphophomenic in nature which means the words are composed of parts that represent both sound and meaning. Therefore, it is necessary to not only strategically address the sounds in words but also the meaning of words, down to their smallest parts. A morpheme refers to the smallest, meaningful unit within a word. Morphemes can be free, meaning they stand alone, or bound, meaning they work in combination with other morphemes. Free morphemes typically include content words such as nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs and function words such as prepositions, conjunctions, pronouns, auxiliary verbs and articles. Bound morphemes include Latin and Greek roots (e.g., Latin: dict which means to say as in predict; Greek: tri, which means three as in triangle). Bound morphemes must be combined with free morphemes to form words. In K-12 education, bound morphemes are often referred to as roots or stems.

Types of Morphology

Three types of morphology have been identified in literature: inflectional, compound and derivational morphology.

- Inflectional morphology refers to how grammatical functions are marked. It includes understanding and use of word formation rules to form simple plurals, verb forms and possessive forms (Kou & Anderson, 2006). In inflected word forms, the word class (or part of speech) stays the same and involves high-frequency, obligatory grammatical suffixes (e.g., -s, -ed, -ing).

- Compound morphology is the process of combining individual morphemes or words that can stand alone to form a new word with a different meaning. For example, in compounding, the words rain and bow both refer to two different items. One refers to visible drops of condensed moisture that fall from the sky. The other refers to a knot tied with two loops and two loose ends. By combining these two words together (rain + bow) we get a new word form, rainbow, with a completely different meaning.

- Derivational morphology refers to the basic units of word formation and the principles that guide their combination (Tyler & Nagy, 1987). Derivational morphemes change the part of speech when added to base or root words. Acquiring knowledge of derivational morphology is typically a longer process than acquiring inflectional or compound morphological knowledge, continuing to develop even into adulthood. Three types of derivational morphology knowledge have been documented- relational, syntactic, and distributional knowledge (Tyler & Nagy, 1987).

Types of Derivational Morphology

- Relational knowledge refers to the ability to recognize the stem of morphologically complex words and understand the relationship between the stem and the suffix, in other words, knowing where derived words come from. For example, understanding that the word painter comes from paint or width comes from wide would imply that one has relational knowledge.

- Syntactic knowledge refers to the ability to identify the part of speech of a word after the suffix has been added. For example, if the suffix -able is added to the word collect, it becomes collectable. While collect standing alone is a verb, adding the suffix able changes collect to collectable, transforming it to a noun.

- Distributional knowledge refers to the ability to understand how affixes are constrained by the syntactic category of the stem. In other words, knowing which prefixes and suffixes can be added to certain words and which ones cannot is an indication of one’s distributional knowledge. For example, the prefix re- can be added to the words model and play to form remodel and replay but re cannot be added to the words chair or door to form *rechair or *redoor.

Morphological Awareness

Simply put, morphological awareness is the ability to manipulate morphemes and employ word formation rules. More explicitly, morphological awareness is described by Apel (2014) as an awareness of the following: 1) spoken and written forms of morphemes, 2) the meaning of affixes (prefixes and suffixes) and the changes in meaning and grammatical class they bring to base words/roots, 3) how written affixes connect to base words/roots, and 4) the relationship between base words/roots and their inflected or derived forms. Morphological knowledge begins to develop as early as the preschool years and most children are able to verbally express themselves using appropriate grammatical forms; however, they are usually not aware of the rules that dictate that usage.

Why morphological awareness is important for reading and writing

Approximately 80% of English words are morphologically complex (Anglin 1993; Hiebert, Goodwin, & Crevetti, 2018). When learners encounter unfamiliar words, they attempt to look for recognizable parts of words to adequately decode text tapping into knowledge from various systems-linguistic (phonological, morphological and syntactic), orthographic (word identification and recognition), and lexical (word meaning). These same systems activated for decoding (reading) are also activated for encoding (spelling) in reverse order. Therefore, Morphological awareness impacts word reading, reading comprehension and spelling (Carlisle, 2003; Denston et al., 2018; Levesque et al., 2021). Morphological awareness is also associated with word reading and spelling from first grade and beyond, and by at least second grade, morphological awareness is more strongly related to reading comprehension than other language or reading skills such as phonological awareness (for a review, see McBride, 2016). Additionally, studies show evidence of the influence of morphological awareness in the development of vocabulary knowledge (Bowers et al., 2010; McBride-Chang et al., 2008; Pan et al., 2023); and reading subskills such as lexical inferencing, spelling, and word identification (Ke & Xiao, 2015). Learners rely on their knowledge of the morphological structure of words as they interact with print-reading or writing-as they work to understand or generate ideas. Literacy learners benefit from explicit instruction in meaningful word parts. There is a bidirectional association between morphological awareness in language and literacy development (Levesque et al., 2021) which should be supported through a structured literacy approach based on the science of reading.

How morphological awareness contributes to reading and writing

Previous research provided ample evidence of the influence of morphological awareness on the development of specific literacy skills, but questions remained as to how. Levesque, et al. (2021) provided a Morphological Pathways Framework to help explain how morphological awareness contributes to reading and writing. In this framework, the relationship between reading and spelling is explicit, implicit and bidirectional between several systems-linguistic, orthographic, and lexical. The linguistic system supports development of the orthographic system where children learn letter-sound mapping of syllables, morphemes, and whole words. Learners retrieve orthographic (spelling) and phonological (sound) units for reading and spelling through the central orthographic processes. In turn, the orthographic system supports the development of the linguistic system. This process facilities the learner’s ability to engage in morphological decoding and word identification during reading. The linguistic system also supports k-12 learners’ ability to engage in morphological analysis (breaking words down into meaningful parts). Since morphemes carry meaning, morphological analysis facilitates the learner’s understanding of word meaning by examining the individual parts, increasing word level comprehension and expanding vocabulary knowledge. Expanding the learner’s vocabulary contributes to the development of the linguistic and orthographic systems. Both morphological decoding and morphological analysis facilitate text comprehension supporting the development of general knowledge and written expression. For a complete explanation of the Morphological Pathways Framework see Levesque et al.

Morphological awareness considerations for non-native English speakers

Morphological skills in a first language can sometimes facilitate language and literacy learning in a second language (e.g., Deacon et al., 2007; Koda, 2000; Leonet, et al., 2020). Therefore, children should be encouraged to develop language skills in their native language as well as the language to be acquired. However, it is important to note that morphological skills important for reading are somewhat confined by the constraints in each language (e.g., McBride et al., 2022). For example, morphological awareness may be measured differently in different languages and can sometimes be more difficult to assess in a foreign language as compared to a first language (e.g., Pan et al., 2023). Nevertheless, explicit instruction in morphology can improve oral and written language skills in learners across languages (e.g., Carlisle, 2010). Despite differences in morphology across languages, morphological awareness contributes to vocabulary development (McBride et al., 2008) and is thought to be a sharable resource across languages, supporting both language and literacy development.

Conclusion

In conclusion, understanding morphology is essential for learners as it significantly impacts literacy development. There are three types of morphology described in the literature: inflectional, compound, and derivational. Three types of derivational morphology include relational, syntactic and distributional. A large majority of words encountered by learners are morphologically complex and require more than letter-sound knowledge. As teachers provide instruction in language, reading and writing with words it is just as important to talk about how those words are formed. Knowledge of morphological structure positively impacts word recognition, vocabulary knowledge, and the ability to comprehension text (Carlisle, 2003, Denston et al., 2018).

References

Apel, K. (2014). A comprehensive definition of morphological awareness: Implications for assessment. Topics in Language Disorders, 34(3), 197–209. https://doi.org/10.1097/TLD.0000000000000019

Anglin, J.M. (1993). Vocabulary development: A morphological analysis. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development 58(10, Serial no. 238) 1-186,, https://doi.org/10.2307/1166112

Bowers, P. N., Kirby, J. R., & Deacon, S. H. (2010). The Effects of Morphological Instruction on Literacy Skills: A systematic review of the literature. Review of educational research, 80(2), 144-179. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654309359353

Carlisle, J. F. (2003) Morphology matters in learning to read: A commentary. Reading Psychology, 24(3-4), 291-322, https://doi.org/10.1080/02702710390227369

Carlisle, J. F. (2010). Effects of Instruction in Morphological Awareness on Literacy Achievement: An Integrative Review. Reading Research Quarterly. 45(4). 464-487. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.45.4.5

Deacon, S. H., Wade-Woolley, L., & Kirby, J. (2007). Crossover: The role of morphological aware-ness in French immersion children’s reading. Developmental Psychology, 43(3), 732-746. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.3.732

Denston, A., Everatt, J., Parkhill, F., & Marriott, C. (2018). Morphology: Is it a means by which teachers can foster literacy development in older primary students with literacy learning difficulties? The Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 41(2), 94-102. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03652010

Hiebert, E.H., Goodwin, A.P. & Cervetti, G.N. (2018). Core vocabulary: Its morphological content an presence in exemplar texts. Reading Research Quaterly, 53, 29-49. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.183

Ke, S., & Xiao, F. (2015). Cross-linguistic transfer of morphological awareness between Chinese and English. Language Awareness, 24(4), 355–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2015.1114624

Koda, K. (2000). Cross-linguistic variations in L2 morphological awareness. Applied Psycholin-guistics, 21(3), 297-320. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716400003015

Ku, Y. M., & Anderson, R. C. (2003). Development of morphological awareness in Chinese and English. Reading and Writing, 16(5), 399-422. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024227231216

Kuo, L., & Anderson, R.C. (2006). Morphological awareness and learning to read: A cross-language perspective. Educational Psychologist, 41(3), 161-180. doi: 10.1207/s15326985ep4103_3

Leonet, O., Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2020). Developing morphological awareness across languages: Translanguaging pedagogies in third language acquisition., Language Awareness, 29(1), 41-59. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2019.1688338

Levesque, K. C., Breadmore, H. L., Deacon, S. H. (2021). How morphology impacts reading and spelling: advancing the role of morphology in models of literacy development. Journal of Research in Reading, 44(1). 10-26. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9817.12313

McBride, C. (2016). Children’s literacy development: A cross-cultural perspective on learning to read and write (2nd ed.). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

McBride, C., Pan, D. J., & Mohseni, F. (2022). Reading and writing words: A cross-linguistic perspective. Scientific studies of Reading. 26(2). 125-138. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2021.1920595

McBride-Chang, C. A., Tardif, T., Cho, J. R., Shu, H. U. A., Flether, P., Strokes, S. F., … Leung, K . (2008). What’s in a word? Morphological awareness and vocabulary knowledge in three languages. Applied Psycholinguistics, 29(3), 437-462. https://doi.org/10.1017/S014271640808020X

Tyler, A., & Nagy, W. (1987). The acquisition of English derivational morphology.

(Technical Report No. 407). Champaign, IL: Center for the Study of Reading.

Pan, D. J., Nakayama, M., McBride, C., Cheah, Z. R. E., Zheng, M., & Yeung, C. C. L. (2023). Cognitive-linguistic skills and vocabulary knowledge breadth and depth in children’s L1 Chinese and L2 English. Applied Psycholinguistics 44(1), 77-99. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716422000480

Practice Brief – Morphological Awareness: An avenue for improving vocabulary, word recognition, spelling and reading comprehension

Chenell Loudermill, Ph.D., CCC-SLP

Clinical Professor, Purdue University

April 2025

Learning requires the integration of many skills, with language development being a crucial foundational aspect. Language development across five domains-phonology (the sounds within a language), morphology (word structure/formation), semantics (word meaning), syntax (sentence structure/grammar), and pragmatics (use in varying contexts)-unequivocally supports the acquisition of reading and writing skills. Specifically, morphological knowledge is vital for improving vocabulary, word recognition, spelling and reading comprehension. This practice brief provides an overview of morphological awareness and derived words, provides a rationale for teaching morphological awareness, and instructional strategies supported by science.

Morphological awareness defined

Morphological awareness is the ability to understand and use word formation rules. Learners must 1) understand the smallest parts of words that carry meaning in spoked and written form (morphemes), 2) understand the meaning of prefixes and suffixes (i.e., affixes), 3) understand that adding affixes to words can change the meaning and grammatical class of the base word, 4) know which affixes can be added to certain words and which ones cannot, and 5) understand the relationship between the base/root word and the derived or inflected forms (Apel, 2014).

English words…Did you know?

Many words in the English language are derived from other languages such as Old English (Anglo-Saxon), Old French (Norman), Latin and Greek. Spelling patterns are influenced by the language of origin; however, they may be modified for visual appearance or to make pronunciation easier. As English words undergo these types of transformations and new words are derived, the ease in which they can be spelled and read varies. Derived words can be classified as transparent, opaque, neutral or non-neutral (Tyler & Nagy, 1989; Windsor,2000) and level of difficulty can be assessed based on this classification. Knowing this information will help teachers better understand why some words are more difficult than others. Read the definitions and say the example words. Listen for the difference in the vowel sounds.

- In transparent words, the base is pronounced the same in the derived word as it is when pronounced without a suffix (e.g., kind; kindness).

- In opaque words, the base undergoes stress and/or vowel changes when pronounced as part of the derived word (e.g., reduce; reduction).

- A neutral suffix attaches to independent words and does not change the stress or vowel quality of the word (e.g., teach; teacher). When a word has a neutral suffix added, the meaning of the derived word is directly related to the stem.

- A non-neutral suffix often attaches to bound morphemes and may change the stress pattern or vowel sound when added to a root (e.g., solid, solidify).

English has a high number of derived words that are morphologically complex. Some morphologically complex words can be described as phonologically transparent, where the base is pronounced the same in the derived word as it is when pronounced without a suffix (e.g., care- careless; Windsor, 2000). There is no vowel sound change.

Some morphologically complex words are phonologically opaque. That means the base undergoes stress and/or vowel changes when pronounced as part of the derived word (e.g., present– presentation; Windsor, 2000).

Morphologically complex words in English can be orthographically transparent, where the base word is spelled the same in the derived word as it is when spelled without a suffix (e.g., play; playful), or they can be orthographically opaque, where spelling changes occur at the end of the word before adding the suffix (e.g., happy; happiness).

Some morphologically complex words undergo both phonological (sound) and orthographic (spelling) changes (e.g., explain; explanation). Words with phonological shifts (e.g., produce; production) tend to be more difficult to learn than words without phonological shifts (e.g., care; careless).

Considering this information when providing instruction in reading and spelling can help teachers understand why learners may be having difficulty with certain words and not others.

Why teach morphological awareness?

Learners who do not have sufficient language skills are at risk of being left behind their peers in the development of vocabulary, word reading, spelling and comprehension without instruction in morphological awareness (Carlisle, 2003). Studies show that instruction in morphological awareness has resulted in positive literacy outcomes for children with and without reading difficulties (see Loudermill et al., 2021 for a review). Using the practical strategies listed below to teach morphology can be beneficial for all learners.

Practical strategies for teaching morphology

When selecting target words to use during morphology instruction, it is important for teachers to consider the how transparent words are. Words that are transparent and stable should be taught before those with obscure meaning. Teachers should also consider how morphemes can be combined to create meaningful words. Those that are used more frequently should be introduced early. Teachers should also consider how complex morphemes are and introduce derived forms that do not shift phonologically or orthographically first (see continuum below). Claravall (2016) and Henry (2017) provided a summary of practical strategies for morphology instruction, some of which are summarized below.

Provide explicit instruction in morphemes. Explicit instruction in morphemes should consist of the specific word part, classification (affix type), the letters, how it sounds when read aloud and the meaning. Instruction should also include what happens when affixes are added to a base word and word origin when necessary. After gradually introducing morphemes through explicit instruction, questioning can be used to reinforce learning until students have reached the desired level of proficiency . When students read words incorrectly, asking questions based on what they know to help them get to the correct answer provides support for students to connect known information to newly learned information. This method is known as the Socratic method and facilitates critical thinking. Questions may address letter names, sounds, pronunciation, affix type (prefix or suffix) and meaning or any combination thereof depending on the level of the learner. Some reading curricula provide a scope and sequence that includes commonly used affixes and suggestions for when to introduce them. One such tool is the Purdue LEaPP Scope and Sequence.

Provide opportunities for morphological analysis. Learners should be provided opportunities to deconstruct (break words apart), construct (build words), define (tell what words mean) and use (generate sentences containing targets) morphologically complex words. Such tasks provide opportunities for explicit, systematic reading and spelling practice. Morphological analysis also provides opportunities for learners to identify part of speech and discuss changes in word class. Instruction in morphological analysis should be fun and engaging for learners. Suggestions to support morphological analysis include creating a morphology journal for students to monitor their progress and engaging students in an engaging activity such as Mucho Morpho. Morphological analysis can occur as early as first grade. Below are examples of morphological analysis tasks by grade level.

First Grade: Teach plurals such as adding s. Example: car + s = cars

Second Grade: Introduce orthographic constraints and shifts. Example: party à parties

Third Grade: Teach more affixes and use in combination. Example: unmatched

Fourth Grade: Teach syntactic constraints. Pre- can only attach to verbs, adjectives, and adverbs

Fifth Grade: Teach advanced derivational morphology. Greek and Latin bases such as ject, dict, bio, tri

Situate morphology instruction in subject matter content. Instruction in morphology can be provided using content from any curriculum. Eighty percent of words children encounter in school are morphologically complex (Anglin, 1993). Therefore, using relevant curriculum-based materials allows authentic reading and writing tasks to serve as a proxy for meaningful morphology instruction. Activities such as word hunts for target morphological concepts within short stories, poems, and reading passages provides one avenue to practice/reinforce morphological awareness. Writing activities requiring learners to use target morphologically complex words in sentences and discussing word origin of base and root words support increasing morphological knowledge. Using www.etymonline.com can provide support for such discussions.

Make use of technology. Using digital technologies can support independent practice and carryover and serve as another means to deliver instruction. Sites such as Reading A-Z and Vocabulary A-Z can offer additional resources to support instruction. It is important for teachers to critically evaluate the content found on sites for appropriateness and to not rely on technology to be the primary mode of instruction.

Additional examples of activities to support morphology instruction for primary and upper grades are listed below.

Example activities for primary grade instruction. Have students to

- Listen for morphologically complex words during oral readings

- Make compound words using familiar single words

- Take words apart; remove inflections and simple suffixes from base words

- Sort past tense and/or plural words by the sound of their ending (e.g., /s/ vs /z/, and the three sounds of -ed)

- Categorize inflected words by meaning and/or class

- Categorize words by form: compound word, contractions, and other

- Establish awareness of the syllables, phonemes, and morphemes in the word

Example activities for upper grade instruction. Have students to

- Learn about schwa developing a foundation for learning about syllable shift in derived word forms and for syllable tracking

- Identify prefixes, roots, and suffixes in words

- Define affixed words

- Proofread and correct misspellings

- Practice word building with one root or combining form

- Build word webs or diagrams that show families of words built from a root (e.g., morpheme matrix)

- Complete cloze passages (fill-in-the-blank) using morphologically complex words (e.g., madlibs)

- Build families of derived words by forming compound suffixes from a base

- Combine base words, prefixes, and suffixes and use the new words

Conclusion

Bowers et al., (2010) provided the quote…

“The ultimate goal of morphological awareness instruction, however, is not for children to learn about [all] morphemes. Rather, it is hoped that explicit morphological instruction will increase understanding about oral and written features of morphology at the sublexical level that, in turn, will influence literacy skills at the lexical level (e.g., word reading, spelling, and vocabulary) and the supralexical level (e.g., reading comprehension).”

To accomplish this goal, it is beneficial for teachers to have a deeper understanding of morphology, derived words, how morphological awareness impacts literacy development and how to structure activities to facilitate understanding of how words work. With this deeper understanding, teachers can critically evaluate curricula, more adequately plan instruction/activities and provide proper scaffolding for learners as they develop skills in vocabulary, word reading, spelling, and reading comprehension.

References

Anglin, J. M. (1993). Vocabulary Development: A Morphological analysis. (cover story). Monographs Of The Society For Research In Child Development, 58(10), 1-166. doi:10.1111/1540-5834.ep9410280902

Apel, K. (2014). A comprehensive definition of morphological awareness. Topics in Language Disorders, 34(3),197–209. https://doi.org/10.1097/tld.0000000000000019

Bowers, P. N., Kirby, J. R., & Deacon, S. H. (2010). The effects of morphological instruction on literacy skills: A systematic review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 80(2), 144-179.

Carlisle, J. F. (2003). Morphology matters in learning to read: A commentary. Reading Psychology, 24, 291-322. doi: 10.1080/02702710390227369

Claravall, E. B. (2016). Integrating Morphological Knowledge in Literacy Instruction: Framework and Principles to Guide Special Education Teachers. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 48(4), 195–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/0040059915623526

Deacon, s. H., Kirby, J. R., & Bell-casselman, M. (2009). How robust is the contribution of morphological awareness to general spelling outcomes? Reading psychology, 30, 301–318.

Loudermill, C., Greenwell, T., & Brosseau-Lapré, F. (2021). A Comprehensive Treatment Approach to Address Speech Production and Literacy Skills in School-Age Children with Speech Sound Disorders. Seminars in speech and language, 42(2), 136–146. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0041-1723840

Henry, M.K. (Spring, 2017). Morphemes matter: A framework for instruction. Perspectives on Language and Literacy. Baltimore, MD: The International Dyslexia Association (pp. 23-26).

Tyler, A. & Nagy, W. (1989). The acquisition of English derivational morphology. Journal of Memory and Language, 28(6), 649-667. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-596X(89)90002-8

Windsor, J. (2000). The role of phonological opacity in reading achievement. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 43(1), 50–61. https://doi.org/10.1044/jslhr.4301.50

Research Brief – The ABCs of Learning the ABCs

Cammie McBride, Ph.D.

Associate Dean for Research and Distinguished Professor, Purdue University

Jennifer Schumaker

Senior Research Associate, Purdue University

June 2025

A fundamental aspect of learning to read is mastering the ABCs. This includes recognizing the letter names and their corresponding sounds. In some classrooms, the focus is on memorizing each letter name and sound, with equal attention to each letter. Researchers have demonstrated that children’s letter learning is influenced by many factors. Some of these may be obvious, but others are less so. Understanding how letter learning takes place is practically useful as parents and teachers impart this critical skill to their children (McBride, in press).

What influences mastery?

What influences children’s mastery of letter names and recognition of letters? For any given child, letters are easier to recognize when they are

*In the child’s own name. This is a biggie. We naturally learn things better when we can relate them to ourselves. Children are likely to pay more attention to letters in their own names (Treiman et al., 2001), especially the first letter in their own names (Justice et al.,2006; Puranik et al., 2014).

*Distinctive in look. There is a reason that some ABC books create elaborate artwork around letters. The letter S can be made to look like a snake, and M can represent two mountains (Ehri, 2013). There is even some evidence that children find symmetric letters easier to learn than asymmetric ones (e.g., Yin & McBride 2023). Symmetric ones can be divided in half and still look the same. Examples are O, T and X. Letters that can be linked to a picturable object are easier to recognize and are made more concrete for children.

*More accessible in memory. Here, we invoke the “ABC” song and consider some renditions of it. Have you ever heard children singing this song, confident in the beginning (ABC…) but also the end (XYZ) and not so much in the middle? From the field of memory research, we know that there is both a primacy and a recency effect for human memory: If you are given a long list of things to remember, you are most likely to remember the first 2 or 3 and the last 2 or 3 but fewer items in the middle. It’s the same with the letters of the alphabet (McBride-Chang, 1999; Worden & Boettcher, 1990). One practical implication of this is that children may need less time to learn the first and last three letters of the alphabet and need to spend more time on those in the middle.

*Less confusable. Children are often confused by letters that somehow have a mirror image of themselves, such as b and d, and p, and q (Bornstein et al., 1981; Dehaene, 2010). In nature, we tend to view objects that are presented in left vs. right profile as the same object (e.g., a tree from the left or right perspective). In contrast, objects that are upside down are clearly different from those that are right side up, such as p and b, and M and W. This is one explanation for why it is particularly difficult to distinguish (and learn to write) letters that have mirror images of one another; b and d, and p and q. Children need a lot of practice in distinguishing these (Treiman and Kessler, 2011).

Apart from learning to recognize and write letters, children need to understand connections of these letters to their sounds. What influences the extent to which letter sounds can be learned? Sounds are easier to map to letters when the name of the letter begins with the sound it makes (McBride-Chang, 1999; Treiman & Broderick, 1998; Treiman & Rodriguez, 1999; Treiman et al., 2001). This applies to letters like T, P, B, or Z. In order to pronounce any of these letters, one must use the sound that it makes. T starts as /t/ and Z as /z/. There are other letters that have some connection to their sounds, but this connection is at the end of the letter name. This applies to letters such as L, M, N, and R. The sounds made by these letters end the letter name. For example, L is pronounced as el and N as en. English speakers are primed to focus on the first sound in a word and less primed to focus on the final sound in a word (e.g., McBride-Chang, 1999). Finally, there are letters that have no link to their sound. This applies to H, Q, and W. Sounds made by these letters are more difficult to learn because the sounds have no connection to their pronunciations. (Witness the child who thinks that W makes the /d/ sound, for example.)

There are practical implications of this information. In particular, it is easiest to learn letters whose names start with their sounds (e.g., B, D) and most difficult to learn letters with no connections between letter name and letter sound (e.g., W, Q). Thus, again, rather than spending equal time on all letter names and sounds, it is better to spend more time on the difficult ones and less time on the easy ones (McBride-Chang, 1999; Treiman et al., 1994).

Advice on letter learning

Because learning letter names and letter sounds are similar but not the same activity, our advice on letter learning addresses learning letter names and specific letter sounds.

*Learning letter names. Make sure children engage concretely in letter activities such as identifying letters in both capital and small forms and across fonts. In addition, helping children to create letters and notice their forms helps to make letters, which are somewhat abstract concepts—symbols, more concrete. Focusing on the letter that begins one’s name makes it much more real and easy to remember. We also advocate for singing and reciting the alphabet song in video form in order to link the name and appearance of letters easily. Sesame Street and many other educational programs do this very well, and this is useful for reinforcing early learning.

*Learning specific letter sounds. Reading alphabet books with an emphasis on phoneme awareness helps build the letter sound connection (Brabham et al., 2006), but it is important to understand something about phonological awareness. Children’s awareness of phonemes, or individual speech sounds, is easier to facilitate when the phoneme is presented alone, rather than within a consonant cluster (Treiman & Weatherston, 1992). It is easier to hear the /t/ sound in tap than in trap because the /t/ sound in trap gets lost in the cluster. Therefore, when presenting the connection between letter names and sounds, we prefer to associate the letter with a word that does not begin with a consonant cluster. To hear the /s/ sound clearly, for example, it is easier to say that S is for sun than S is for snake. Similarly, F is for fan is better than F is for flower. In both examples, it is easier to hear the letter sound when it is followed directly by a vowel than a consonant.

As the Science of Reading (SoR) research often reminds us, English is complicated. The ideas presented above will not always be easy to implement in the classroom. However, knowing some of these fundamentals about human cognition and learning as applied to the alphabet can be useful for planning. Rather than spending one week on each letter, it is probably more efficient to spend more time in teaching the appearances and sounds of tricky letters—letters that are more confusable either in appearance or in sound-letter name connection.

References

Bornstein, M. H., Ferdinandsen, K., and Gross, C. G. (1981). Perception of symmetry in infancy. Developmental Psychology 17, 82–86. https://doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.17.1.82

Brabham, E. G., Murray, B. A., & Bowden, S. H. (2006). Reading alphabet books in kindergarten: Effects of instructional emphasis and media practice. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 20, 219-234.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02568540609594563

Dehaene, S., Nakamura, K., Jobert, A., Kuroki, C., Ogawa, S., & Cohen, L. (2010). Why do children make mirror errors in reading? Neural correlates of mirror invariance in the visual word form area. NeuroImage (Orlando, Fla.), 49(2), 1837–1848.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.09.024

Ehri, L. C. (2013). Orthographic Mapping in the Acquisition of Sight Word Reading, Spelling Memory, and Vocabulary Learning. Scientific Studies of Reading, 18(1), 5–21.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2013.819356

Fischer, J. P. (2018). Studies on the written characters orientation and its influence on digit reversal by children. Educational Psychology, 38, 1–16. https://doi: 10.1080/01443410.2017.1359239

Justice, L. M., Pence, K., Bowles, R. B., & Wiggins, A. (2006). An investigation of four hypotheses concerning the order by which 4-year-old children learn the alphabet letters. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 21(3), 374–389.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2006.07.010

Puranik, C. S., Petscher, Y., & Lonigan, C. J. (2014). Learning to write letters: Examination of student and letter factors. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 128, 152–170.

https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.jecp.2014.07.009.

McBride, C. (In press). Children’s Literacy Development: A Cross-cultural Perspective on Learning to Read and Write (3rd ed.). Routledge.

McBride-Chang, C. (1999). The ABCs of the ABCs: The development of letter name and letter sound knowledge. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 45, 285–308.

Treiman, R., & Broderick, V. (1998). What’s in a name: Children’s knowledge about the letters in their own name. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 70, 97–116.

https://doi.org/10.1006/jecp.1998.2448

Treiman, R., and Kessler, B. (2011). Similarities among the shapes of writing and their effects on learning. Written Language & Literacy, 14, 39–57. https://doi: 10.1075/wll.14.1.03tre

Treiman, R., Sotak, L., & Bowman, M. (2001). The roles of letter names and letter sounds in connecting print and speech. Memory & Cognition, 29, 860–873.

https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03196415

Treiman, R., & Weatherston, S. (1992). Effects of linguistic structure on children’s ability to isolate initial consonants. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(2), 174.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.84.2.174

Treiman, R., Weatherston, S., & Berch, D. (1994). The role of letter names in children’s learning of phoneme–grapheme relations. Applied Psycholinguistics, 15(1), 97–122.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716400006998

Yin, L., & McBride, C. (2023). A longitudinal study on sensitivity to symmetry in writing and associations with early literacy abilities. Frontiers in Education (Lausanne), 8.

https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1150075

Practice Brief –Neurodiversity in Action Understanding the brain basis of dyslexia

Rebecca A. Marks, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor, Purdue University

July 2025

Dyslexia, a specific learning disability (SLD) characterized by word reading impairment, is commonly misunderstood as a disorder in which learners simply reverse their letters, like b and d. Research in cognitive neuroscience tells a different story, and can help us to target our instruction to better serve struggling readers.

The reading brain

Reading involves integrating brain systems for language with brain systems for visual perception. A 5-year-old child comes to the task of learning to read with years of language experience; learning to read involves connecting their knowledge of the sounds and meanings of language to printed symbols on a page.

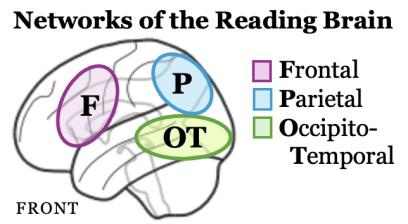

The reading brain can be broken down into three main systems that work together in a larger network. The frontal circuit (purple) analyzes the sounds within words; the parietal circuit (blue) connects sound, meaning, and print; and the occipito-temporal circuit (green) supports fluent, automatic visual word recognition. Early reading relies heavily on the frontal regions of the brain to support effortful phonological decoding. Skilled readers still use this frontal network, but rely more heavily on regions in the back of the brain, reflecting efficient connections between word meaning and printed form.

Defining dyslexia

Dyslexia is characterized by persistent difficulties in accurate and/or fluent word reading despite adequate instruction and intelligence. There is no single root cause of dyslexia, and children with dyslexia have a wide range of cognitive profiles. One frequent struggle is in phonological processing, or the ability to accurately perceive and manipulate the sounds of language. Many children also struggle with rapid automatized naming, or RAN, which assesses the speed of naming familiar items like letters or numbers. Dyslexia also has high heritability, which means that it has a genetic component and runs in families (Doust et al., 2022).

The cognitive neuroscience of dyslexia

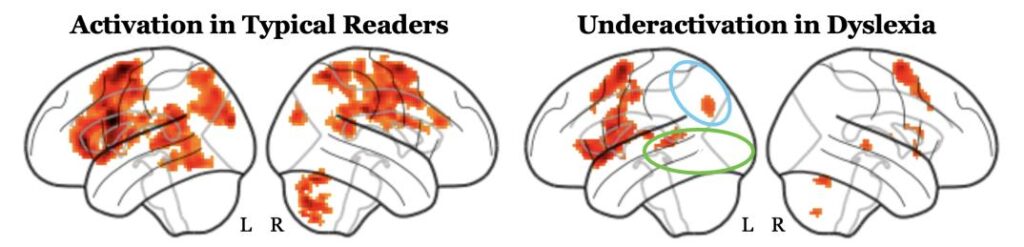

Research in cognitive neuroscience has revealed differences in brain responses to spoken language as well as written language (D’Mello & Gabrieli, 2018). On average, individuals with dyslexia under-activate the parietal (blue) and occipito-temporal (green) regions at the back of the brain that support connecting letters and sounds to print. These brain differences are present long before children learn to read. Studies have found that infants who are diagnosed with dyslexia many years later show neurocognitive differences in their responses to speech sounds as infants (Leppänen et al., 2002; Yu et al., 2018).

It is important to understand that these brain differences in dyslexia are based on group averages. Our most advanced science to date cannot determine whether or not an individual has a reading disorder based on a brain scan alone. This is because there is so much variability in the patterns of brain activity within groups of readers, both skilled and impaired.

Consider this analogy: A class of second graders will be shorter on average than a class of third graders. Even so, if all you know about a child is their height, you couldn’t reliably place them in the correct grade. Likewise, an individual brain image is insufficient to diagnose dyslexia.

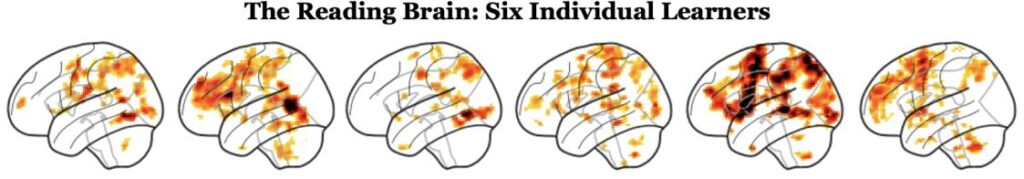

Pictured below are brain activations in the left hemispheres of six children (grades 3–5) during fMRI neuroimaging. Each child completed a task that involved reading two words and deciding whether they rhyme (e.g., ocean | motion). The images below show the regions of the brain that were more active during this reading task than during a non-reading task.

Of the six brains above, half belong to children who are reading at grade level. The other half are struggling readers with dyslexia. We can’t tell from a brain image alone whether a child has dyslexia.

When combined as a group, general patterns of under-activation in dyslexia become clearer. Below is the result of averaging brain activations during word reading from 50 typical readers on the left, and 63 readers with dyslexia on the right. We can see reduced engagement on average in the parietal (blue) and occipito-temporal (green) regions.

How can neuroscience inform practice?

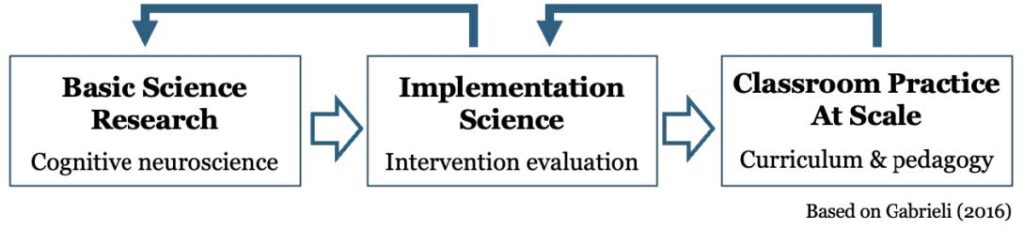

Cognitive neuroscience is one piece of a much larger puzzle informing approaches to education. Neuroscience tells us about the mechanisms underlying reading development and learning differences. When we understand these mechanisms, we can target instruction to support them.

Many dyslexic individuals describe experiences of “word blindness,” or feeling as if words and letters swim in front of their eyes as they try to read. The idea that dyslexia is, at its core, related to oral language rather than vision may feel counter-intuitive. Neuroscience revealed, for the first time, that dyslexia was associated with differences in auditory phonological processing, even in the absence of print (Kovelman et al., 2012).

Building on this knowledge, we can prioritize reading instruction that best supports the brain mechanisms that differ in dyslexia. Children who go on to develop dyslexia show reduced brain responses during phonological processing long before they learn to read (Leppänen et al., 2002; Yu et al., 2018). Armed with this understanding, we can provide systematic, explicit instruction that supports phonological decoding. Optimal early reading instruction builds automaticity in word recognition, allowing children to reallocate brain resources away from effortful decoding and towards meaning-making.

Best practices in reading instruction

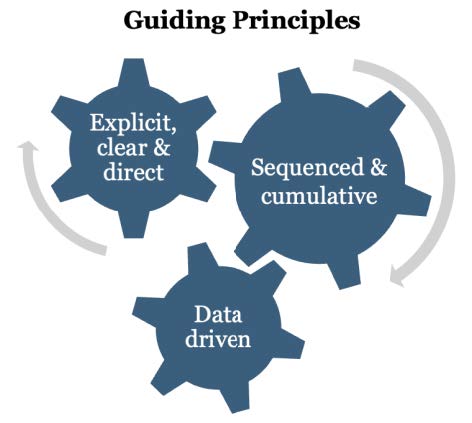

The cognitive neuroscience of reading provides little direct insight into classroom practice. However, following the guiding principles below may help teachers and clinicians to best support their struggling learners. Ideally, instruction should be:

like the gears of a machine.

Explicit, clear, and direct:

- De-mystifies relationships between sounds and letters

- Breaks words down into their meaningful parts

- Teaches oral language skills and relates them to reading, e.g., comparing spoken sentences to the complex syntax often found in academic texts

- Models skills and provides opportunities for practice

Sequenced and cumulative:

- Follows a logical scope and sequence that allows students to build on their learning over time

- Builds on students’ growing vocabulary and background knowledge

Data driven:

- Informed by ongoing low-stakes assessment

- Uses student data to track learning progress and target areas of challenge

Further Reading

To learn more about the brain basis of dyslexia:

Kearns, D. M., Hancock, R., Hoeft, F., Pugh, K. R., & Frost, S. J. (2019). The neurobiology of dyslexia. Teaching Exceptional Children, 51(3), 175-188.

To learn more about Rapid Automatized Naming (RAN) and its role in dyslexia screening:

What Educators Need To Know About RAN (Norton, 2020)

For an overview of explicit instruction in literacy:

Vaughn, S. & Fletcher, J. (2021). Explicit instruction as the essential tool for executive the science of reading. The Reading League Journal, 2(2), 4-11.

References

D’Mello, A. M., & Gabrieli, J. D. (2018). Cognitive neuroscience of dyslexia. Language, speech, and hearing services in schools, 49(4), 798-809.

Doust, C., Fontanillas, P., Eising, E., Gordon, S. D., Wang, Z., Alagöz, G., … & Luciano, M. (2022). Discovery of 42 genome-wide significant loci associated with dyslexia. Nature genetics, 54(11), 1621-1629.

Kovelman, I., Norton, E. S., Christodoulou, J. A., Gaab, N., Lieberman, D. A., Triantafyllou, C., … & Gabrieli, J. D. (2012). Brain basis of phonological awareness for spoken language in children and its disruption in dyslexia. Cerebral Cortex, 22(4), 754-764.

Leppänen, P. H., Richardson, U., Pihko, E., Eklund, K. M., Guttorm, T. K., Aro, M., & Lyytinen, H. (2002). Brain responses to changes in speech sound durations differ between infants with and without familial risk for dyslexia. Developmental neuropsychology, 22(1), 407-422

Yu, X., Raney, T., Perdue, M. V., Zuk, J., Ozernov‐Palchik, O., Becker, B. L., … & Gaab, N. (2018). Emergence of the neural network underlying phonological processing from the prereading to the emergent reading stage: A longitudinal study. Human brain mapping, 39(5), 2047-2063.

Linguistic Knowledge for Teachers:

Supporting Multilingual Learners in the Science of Reading Era

Brenda Sarmiento Quezada, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor, Purdue University

Introduction

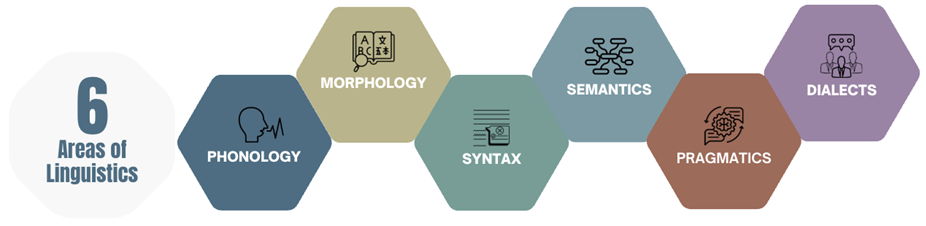

The Science of Reading (SOR) is intended to benefit all children as they develop foundational skills in reading. For students who bring proficiencies in languages and dialects other than Standard English, their experience of SOR instruction often differs. These learners draw upon diverse linguistic repertoires, ranging from varied sound systems to complex morphological and syntactic structures, that shape how they engage with classroom activities such as phonics, decoding, and comprehension. This research brief highlights the importance of teachers’ linguistic knowledge in ensuring that SOR-aligned instruction distinctly and equitably serve multilingual learners. The brief provides an overview of six areas of linguistics (Figure 1: phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics and pragmatics, and dialect awareness) that are directly connected to reading instruction. Each section reviews why these areas matter for literacy development and offer practical implications for classroom practice.

Core Areas of Linguistic Knowledge Teachers Need

Phonology

Phonology refers to the sound systems of languages. In reading instruction, phonology is tied to phonemic awareness (the ability to identify and manipulate sounds in spoken language) and phonics (the mapping of sounds to print). English has a relatively large and complex inventory of vowel and consonant sounds compared to many other languages . For example, in Spanish there are five pure vowel sounds (/a/, /e/, /i/, /o/, /u/) that are always pronounced the same way, regardless of context. In contrast, English vowels have multiple pronunciations depending on their position and surrounding consonants (e.g., the “a” in cat, cake, and car). This variability in English vowels creates additional challenges for multilingual learners whose home language vowels map consistently.

Why it matters for reading

Multilingual students’ knowledge of sound systems in their home languages shapes how they acquire English phonics. For example, Spanish-speaking children may not distinguish between short and long vowels in English, while students whose languages lack the “th” sound (e.g., Korean, Gujarati) may substitute other sounds. Such transfer patterns are normal, not errors, and influence how students decode and spell in English (Cummins, 2001, 2021; Shanahan & Beck, 2006). Teachers who understand these differences are better able to distinguish between language transfer and genuine reading difficulties

Practice implications

- Provide explicit instruction in sounds unique to English;

- Use visual/tactile supports (e.g., mouth diagrams, hand signals) to demonstrate articulation;

- Highlight similarities and differences between English and students’ home languages; and

- Focus on consistent sound–symbol mapping rather than accent.

Morphology

Morphology is the study of word parts, such as roots, prefixes, and suffixes, and how they combine to form meaning. Morphological awareness plays a critical role in vocabulary, word recognition, spelling, and reading comprehension.

Why it matters for reading

Research shows that explicit morphological instruction improves reading outcomes for multilingual learners. Spanish-English bilinguals, for example, benefit from cognates and shared affixes across languages, which facilitate cross-linguistic transfer (Ramirez et al., 2013). For instance, teaching the root tele- (meaning “distance”) helps students recognize connections across words like telephone, television, and telegraph. Spanish speakers can also connect this to the cognate teléfono, reinforcing meaning while building decoding skills. Similarly, highlighting suffixes such as -ción in Spanish and -tion in English helps students see how word families span across languages. Instruction that emphasizes morphemes helps students decode complex words, expand vocabulary, and strengthen comprehension (Kim et al., 2015; Koda & Zehler, 2008).

Practice implications

- Teach common roots, prefixes, and suffixes in both English and students’ home languages;

- Leverage cognates to expand vocabulary (e.g., familia/family);

- Encourage word analysis strategies for decoding multisyllabic words; and

- Integrate morphology into spelling and reading and listening comprehension instruction.

Syntax

Syntax is the set of rules that govern sentence structure. Reading comprehension depends on students’ ability to parse and make sense of increasingly complex sentences found in academic texts. For example, English texts often use embedded clauses, such as “The boy who was wearing a red hat ran quickly.” Students whose home languages typically use shorter or less embedded structures (e.g., in Mandarin or Spanish) may initially struggle to keep track of the main idea while processing the additional information. Explicitly teaching students to identify the main clause and supporting details can help them better understand these kinds of sentences.

Why it matters for reading

Multilingual bilingual students often need support with English syntax, which can differ significantly from their home language structures. For example, adjective–noun order (e.g., “red car” in English vs. “carro rojo” in Spanish) or subject–verb agreement can impact listening and reading comprehension and writing. Explicit instruction in syntax improves students’ ability to navigate complex texts and supports higher-level reading comprehension (Cummins, 2005; Escamilla et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2015).

Practice implications

- Break down and model complex sentences from grade-level texts;

- Provide sentence frames and stems to scaffold comprehension and production;

- Compare and contrast sentence structures in English and students’ home languages; and

- Use oral language practice (e.g., retelling, paraphrasing) to strengthen syntactic awareness.

Semantics and Pragmatics

Semantics refers to how words and sentences convey meaning, including vocabulary knowledge, multiple-meaning words, and relationships among words. Pragmatics refers to how language is used in context, such as making inferences, understanding figurative language, and shifting between informal and academic registers. For example, a child learning English may read the sentence “It’s raining cats and dogs” and picture animals falling from the sky. Without explicit instruction in idiomatic language and pragmatic use, the intended meaning (“It’s raining heavily”) can be lost, which affects comprehension.

Why it matters for reading

Vocabulary and comprehension are core pillars of the Science of Reading, yet multilingual learners often face challenges when semantic and pragmatic aspects of language are overlooked. Students may misinterpret words with multiple meanings (e.g., “bat” as an animal vs. a sports tool), struggle with false cognates (e.g., embarazada in Spanish meaning “pregnant,” not “embarrassed”), or miss pragmatic cues in figurative expressions and idioms. In addition, cultural norms shape how students use and interpret language in different contexts, for instance, expectations about when to speak in class or how to respond to questions. Teachers who understand these layers can better support comprehension and equitable participation (Cummins, 2001, 2021; Duke & Cartwright, 2021; García & Kleifgen, 2019; Lightbown & Spada, 2013).

Practice implications

- Teach multiple word meanings and highlight cross-linguistic similarities and differences, including cognates (words that share meaning and form across languages, such as animal in English and animal in Spanish) and false cognates (words that look similar across languages but have different meanings, such as éxito in Spanish meaning “success,” not “exit”);

- Use texts that include figurative language and model strategies for interpreting idioms, metaphors, and humor;

- Provide explicit instruction in academic register while affirming home and community language practices; and

- Create opportunities for oral discussion that validate diverse pragmatic norms (e.g., turn-taking, narrative styles), ensuring all students can engage meaningfully.

Dialects and Language Variation

All languages have dialects and varieties, including English (e.g., African American English, Appalachian English, Chicano English). These are systematic, rule-governed, and legitimate forms of communication. For example, in Chicano English, a student might pronounce the word school as [es’kul] by adding an initial vowel sound before the /s/ cluster, reflecting Spanish-influenced phonotactics. In addition, Chicano English speakers often use the word barely to mean “just recently,” as in “I barely ate” to mean “I just ate.” Both are features of the dialect, not errors.

Why it matters for reading

Students may bring dialectal features that differ from “standard” school English (e.g., final consonant cluster reduction, habitual “be”). Without linguistic knowledge, teachers may mistake these features for reading errors or deficits. Recognizing dialect differences prevents misidentification of reading difficulties and affirms students’ identities (Aukerman & Chambers Schuldt, 2021; Goldenberg, 2013, 2020;).

Practice implications

- Distinguish between dialect differences and decoding/spelling errors

- Validate students’ home dialects while teaching code-switching for academic contexts;

- Use texts that reflect students’ linguistic and cultural identities; and

- Provide professional development for teachers on dialect diversity and literacy.

Practice Implications for Equitable SOR

Teachers do not need to be linguists or language specialists to effectively apply the Science of Reading with multilingual students. However, developing a working knowledge of how languages differ equips educators to make more informed instructional choices. The following practice implications can support equitable implementation of SOR across linguistically diverse classrooms:

- Phonology: Provide explicit practice with sounds unique to English while drawing connections to students’ home languages. Use visual and kinesthetic supports to reinforce articulation.

- Morphology: Highlight word parts (roots, prefixes, suffixes) across languages. Leverage cognates and word families to expand vocabulary and comprehension.

- Syntax: Scaffold complex sentences from grade-level texts. Compare sentence patterns across languages and use oral language activities to build syntactic awareness.

- Semantics and Pragmatics: Teach multiple word meanings, figurative language, and cross-linguistic similarities/differences. Use culturally responsive texts and explicitly model how language use shifts across contexts (e.g., home vs. school, informal vs. academic).

- Dialects: Recognize dialectal features (e.g., African American English) as systematic, not deficient. Differentiate between variation and true reading difficulties.

These strategies are most effective when embedded in everyday literacy instruction rather than treated as add-ons. Teachers who adopt a linguistically informed lens can better identify transfer patterns, provide targeted support, and build on the full range of students’ linguistic strengths (August & Shanahan, 2006; Wright, 2025).

Conclusion and Implications

Equitable implementation of the Science of Reading requires more than a focus on phonics, phonemic awareness, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. For multilingual learners, teachers’ knowledge of language—across phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, pragmatics, and dialect variation—is essential for interpreting student progress and tailoring instruction. Without this lens, predictable language transfer and dialectal differences may be misidentified as reading difficulties, and opportunities to build on students’ linguistic resources may be missed.

Teacher preparation and professional development must therefore include a stronger emphasis on linguistics for educators. Research has shown that multilingual learners benefit when instruction explicitly connects features of their home languages to English, leverages cross-linguistic transfer, and validates diverse ways of using language (Cummins, 2001, 2021; Escamilla et al., 2014; García & Wei, 2014; The Reading League Summit, 2023; Wright, 2025). Professional learning that equips teachers with this knowledge can help ensure that SOR-aligned practices serve all students rather than reinforcing monolingual, one-size-fits-all approaches.

At the policy and school level, building linguistically informed literacy instruction also requires access to culturally and linguistically responsive curricula, materials that reflect students’ languages and identities, and assessments that recognize difference versus disorder. Supporting teachers in developing this expertise will not only strengthen literacy outcomes but also affirm the identities of multilingual learners, ensuring they are both seen and heard in the classroom.

In short, advancing the Science of Reading in linguistically diverse classrooms depends on preparing educators to see language as a resource. By embedding linguistic knowledge into teacher preparation, professional development, and instructional design, schools can foster literacy instruction that is both scientifically grounded and socially just.

References

Aukerman, M., & Chambers Schuldt, L. (2021). What matters most? Toward a robust and socially just science of reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(S1), S85-S103. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.406

August, D., & Shanahan, T. (Eds.). (2006). Developing literacy in second-language learners: Report of the National Literacy Panel on language-minority children and youth. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Cummins, J. (2001). Negotiating identities: Education for empowerment in a diverse society (2nd ed.). Multilingual Matters.

Cummins, J. (2005). Teaching for transfer: Challenging the two solitudes assumption in bilingual education. In T. Skutnabb-Kangas & H. C. Hornberger (Eds.), Encyclopedia of language and education (pp. 1521-1535). Springer.

Cummins, J. (2021). Rethinking the education of multilingual learners: A critical analysis of theoretical concepts. Multilingual Matters.

Duke, N. K., & Cartwright, K. B. (2021). The science of reading progresses: Communicating advances beyond the simple view of reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(S1), S25–S44. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.411

Escamilla, K., Hopewell, S., Butvilofsky, S., Sparrow, W., Soltero-González, L., Ruiz-Figueroa, O., & Escamilla, M. (2014). Biliteracy from the start: Literacy squared in action. Caslon Publishing.

García, O., & Kleifgen, J. A. (2019). Educating emergent bilinguals: Policies, programs, and practices for English learners (2nd ed.). Teachers College Press.

García, O., & Wei, L. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education. Palgrave Macmillan.

Goldenberg, C. (2013). Unlocking the research on English learners: What we know—and don’t yet know. American Educator, 37(2), 4-11.

Goldenberg, C. (2020). Reading wars, reading science, and English learners. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(51), S131-S144. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.340

Kim, T. J., Kuo, L. J., Ramírez, G., Wu, S., Ku, Y. M., de Marin, S., Eslami, Z. (2015). The relationship between bilingual experience and the development of morphological and morpho-syntactic awareness: a cross-linguistic study of classroom discourse. Language Awareness, 24(4), 332–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2015.1113983

Koda, K., & Zehler, A. M. (2008). Learning to read across languages: Cross-linguistic relationships in first- and second-language literacy development. Routledge.

Lightbown, P., & Spada, N. M. (2013). How languages are learned (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Ramirez, G., Chen, X., & Pasquarella, A. (2013). Cross-linguistic transfer of morphological awareness in Spanish-speaking English language learners: The facilitating effect of cognate knowledge. Topics in Language disorders, 33(1), 73-92. https://www.doi.org/10.1097/TLD.0b013e318280f55a

Shanahan, T., & Beck, I. (2006). Effective literacy teaching for English-language learners. In D. August & T. Shanahan (Eds), Developing literacy in second-language learners: Report of the national literacy panel on language-minority children and youth (pp. 415–488). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

The Reading League Summit. (2023). Joint Statement of The Reading League and NCEL – Understanding the difference: The science of reading and implementation for English learners/emergent bilinguals (ELs/EBs). The Reading League and National Center for Effective Literacy Instruction for English Learner/Emergent Bilingual Students. https://multilingualliteracy.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Joint-Statement_SOR-EL_EB.pdf Wright, W. E. (2025). Foundations for teaching English language learners: Research, theory, policy, and practice (4th ed.). Brookes Publishing.

Practice Brief – A Quick Start Guide to Science of Reading Aligned Textbooks for Literacy Instruction

Melanie Kuhn, Jennifer Schumaker, and Catherine McBride

October 2025

Educator preparation programs (EPPs) across the country are shifting their literacy curricula to align with the research-based approaches of the “Science of Reading” (SoR). With this change comes the challenge of selecting textbooks and other course materials that will ensure effective classroom practices. This brief aims to provide a quick starting point for identifying literacy textbooks and materials. The books listed in this brief were part of a discussion at The Reading League – Indiana Higher Education Collaboration during its September 2025 meeting. Colleagues from different disciplines shared their interests and preferences for books to teach reading, both at basic and more advanced levels. The Reading League has colleagues in the areas of literacy/reading education, curriculum and instruction, special education, speech and hearing sciences, human development and family science, early childhood education, and other specialties. We teach undergraduate and graduate courses. Our list is not by any means comprehensive, and we acknowledge that what works for one course or audience may not work for another. This list begins with comprehensive textbooks that focus on building the foundation for SoR-aligned literacy instruction. The list then provides more information on specific areas of literacy learning. Please note that the ratings from the National Council on Teaching Quality (NCTQ) (n.d.) are listed in parenthesis between the title and author(s) whenever possible. NCTQ has a 3-point rating scale. According to their scale, a 1 indicates that the book is unacceptable according to certain SoR standards that they have set. Two as a rating indicates that the book is acceptable according to these standards. A label of “exemplary” is given for books with a 3 on this scale. Please keep these in mind as you consider these books. Also, please note that some of these books have not been rated by NCTQ or, in certain circumstances, not all editions of the book have been rated. We have indicated the closest rated edition’s rating in these cases, and we have labeled unreviewed books as (not reviewed). The popularity ranking seems to be based on the number of identified courses that use a particular book out of the 1961 materials reviewed.

Comprehensive Textbooks